His name is Dominique Robert. He spent two months of his summer holidays at Club Med during the 1960s and 70s, as a sailing instructor (at 15, he was the youngest sailing instructor at Club Med) or a sound instructor.

Recently, he returned to the abandoned village of Caprera in Sardinia, closed since 2007, to photographically document the site, in an "urban exploration" style, before everything disappears, which is almost certainly the intention of the Natural Park within whose boundaries the village lies. It's simply a matter of money, but this will undoubtedly happen as soon as the necessary funding is secured.

Following this moving return to a village he knew so well nearly fifty years ago, he wrote a two-part account, richly illustrated with photographs of the site.

Here is the first part of his report.

Enjoy!

Some photos in this report can be viewed in full size. To do so, simply click on the image; a pop-up window will open!

Fifty years later, what remains?

The village of huts of Caprera (Sardinia)

Created in the late 1950s based on the concept that made the Club successful in its early days (a dream location, an all-inclusive package covering everything from sports to food and drink – except for drinks at the bar – with minimal hotel services to maintain profitability), Caprera had been operating for about fifteen years when I spent my first summer there. I was 12 years old, and my mother seemed quite worried when she showed me, in a French newspaper obtained by some unknown means (because that was also the miracle of the Club, back then, to make you exist and have fun completely outside of place and time), an article recounting the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Russian army.

This meant that the Club's "heroic era" was over, and that it was entering a phase of "early maturity." This didn't prevent it from having village leaders like Avner Gruszow (Cefalù, 1966 or 1967), a Zionist activist affiliated twenty years earlier with the "Stern Gang," who had committed numerous anti-British attacks in what would become the State of Israel. He had even been sent to London in 1948 to assassinate the Foreign Minister (and narrowly missed). He recounted all of this in * A Time to Kill, A Time to Build* , but despite this checkered past, he had managed to win the trust of Father Trigano, who entrusted him with villages, GO teams, and thousands of GMs without the slightest hesitation. And since he was rarely wrong, history, here too, has proven him right. A certain Shalom Hassan, who was to become one of the great figures of the Club, was its head of sports in Cefalù.

In the summer of '68, in Caprera, Shalom had become village chief, his wife Maya head hostess, and the gentle, bearded giant Czopp (pronounced "Chopp"), head of sports and volleyball expert on the clay courts located at the heart of the village, under the pine trees, between the bar and the restaurant—a place where everyone inevitably stopped to admire the sporting feat, whether coming back from the beach or coming down from their bungalows to go to dinner, freshened up. The bar necklaces (much more festive than the "bar booklets" of the winter villages, with their flimsy paper tickets) only contained three kinds of balls: white, café au lait, and black, the most expensive. The gold ones would only be created later, thanks to inflation.

It was also that summer that, as I wrote in *My Summers at the Club*, a story published a few years ago on macase.net, I took on the responsibilities of a "quasi-Sailing Club Organizer" for the first time, even if, initially, they only consisted of taking registrations for the Club Managers and forming balanced crews for the 420s, 445s, and other 485s that were hauled up after each regatta onto the cradles of straps set up on the narrow concrete quay, practically at the foot of the first berths. It wasn't much, even though I was quite young to be doing it; it relieved the "real" Sailing Club Organizers, and I was as proud as a peacock!

It was very by chance that I learned, at the beginning of 2015, that is to say almost half a century after my first stay, that Caprera was no longer being operated, which did not surprise me, the hotel orientation taken by the Club being little compatible with the relative austerity of the huts, none of which, let us remember, were even designed to lock: you had to think about bringing your own pitons (with the drill to drive them in) and your padlock if you wished… What surprised me more was that, although a natural park had been created encompassing the island of Caprera, the authorities had left the village abandoned as it was, for lack of financial means to destroy it, and of legal means to force the Club to do so, its long-term lease having in the meantime expired. In short, between the inertia of local public authorities (the Italian islands are very regionalized) and the distance from Rome, the village was slowly sinking into oblivion, rotting away on its feet, until the day when, perhaps, a helping hand would come to put an end to this long and silent agony, and erase it forever from the map.

It was then, in a matter of minutes, in the depths of a long, misty, and cold winter evening near Lyon, that a conviction took root within me, a conviction that suddenly became undeniable: before the village of Caprera disappeared or was too disfigured by the passage of time, I had to return to photographically document what remained of this part of my past, of those incredibly rich and wonderful weeks I had spent there, so formative for me, then on the cusp of adolescence. More than ten years later, as I wrote in * My Summers*, I returned, and there too, memories had accumulated, memories that a return visit would allow me to exorcise.

Preparing for a trip, as everyone knows, is already part of the journey, and thanks to the internet, preparation today can be easily thorough and detailed. Before leaving, I therefore closely studied satellite photos on Google Earth, as well as those published by internet users who had frequented the village before its closure, or who had passed through the area since. Thanks to these images, as well as a few contacts I made by email, I acquired the only certainty that mattered to me: it shouldn't be difficult to physically access the village. For example, from the beach, only a flimsy plastic barrier, barely more than a meter high, blocked access. If necessary, I would bring my trusty Leatherman, which I knew how to use, in the worst-case scenario, to commit the trespassing I was quite prepared to do in the interest of photographic documentation and the duty to remember! Little did I know how right I was… but let's not get ahead of ourselves.

So I arrived in Sardinia, more precisely in La Maddalena, on a perfectly ordinary (and deliberately chosen) weekday evening at the end of April 2015. Too early in the season for the first holidaymakers to be there and interested in my activities, but late enough to be practically guaranteed typical Sardinian weather: sun, beautiful light, not too hot. Yeah, right! When I landed in Alghero, I was greeted by rain, even though I had just left Lyon where the sun was shining brightly!

Landscape gardeners in Brittany know this well: nothing creates beautiful light like the alternation between showers (even slightly prolonged ones), and clearings, and that evening, on the ferry that was taking me from Palau to La Maddalena, I took advantage of the opportunity.

A smoky sky over the mouths of Bonifacio

A smoky sky over the mouths of Bonifacio

Chaotic skies above La Maddalena

Chaotic skies above La Maddalena

The next morning, the rain was still falling, persistent and relentless. Judging by the state of things, it had been raining all night, and I wondered if the dirt track leading to the small beach at the Club, Cala Garibaldi, which was now open to everyone (in Italy, the car is king), had turned into a quagmire. To avoid such an eventuality, I had tried to rent a 4x4, but to no avail; I had only managed to get one of those trendy "crossovers" that are nothing more than slightly raised everyday sedans. In any case, by late morning, the rain seemed to lessen in intensity, even stopping completely at times. So I set off.

Caprera and La Maddalena, two islands that almost touch, have always been linked by a bridge. The very old, very narrow, and very rusty one I knew was recently replaced by a modern, small, curved structure, somewhat in the flattering style of Calatrava. I crossed without stopping; my memories awaited me further on.

After straining my eyes on Google Earth, I had memorized the exact route to what had been the village's "gateway" (a few rare GMs, mostly Italians, came by car), before joining the sandy track to Cala Garibaldi. Soon, I arrived at a low wall and a small, closed gate. The hut that must have housed the caretaker was silently decaying, a tattered Italian flag flapping in the wind. The sky was very gray, and the rain started up again at times.

The closed gate of the abandoned village…

The closed gate of the abandoned village…

Through the foliage, the gatekeeper's hut and a tattered Italian pennant

Through the foliage, the gatekeeper's hut and a tattered Italian pennant

I waited a while for the rain to stop, devouring a salami sandwich I'd made that morning at my local breakfast buffet, then decided to take a closer look. The low wall was ridiculously easy to climb; in fact, it was little more than a matter of stepping over it, and approaching the village "from behind" could contribute to greater discretion. The car was parked sheltered by vegetation, out of sight of the road. Of course, if you came right up to the gate, you couldn't miss it, but any passerby could just as easily have left it there without actually entering the old Club village… A prominent sign proclaimed that the area was under video surveillance, so I carefully inspected the surroundings for a camera and found none: it was just for show, and it would take more than that to deter me. I "climbed over" without difficulty; I was there.

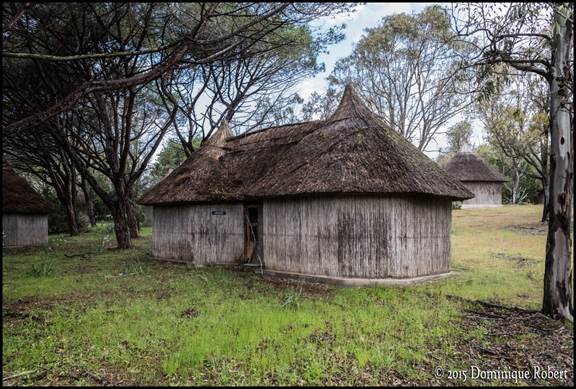

What surprised me most at first was the vegetation. Except under the pine grove, where I knew that not much grew through the thick carpet of pine needles, I had expected to encounter, here and there, a veritable jungle: in seven years of neglect, things grow remarkably well, as the garden can attest every spring! Yet here, the grasses remained perfectly manageable, almost disciplined. I attributed this to the summer droughts, which must have quickly ruined the growth efforts initiated in the spring. The other surprising thing was the pervasive greenery: I suddenly realized that I had only ever known Caprera in the heart of summer, when the gardeners spared no effort (and the drinking water brought from Sardinia by tanker ships to the small concrete jetty that marked the Club's perimeter) to keep a few square meters of lawn and flowers alive at the restaurant or near the bar; Everywhere else, it was a uniform yellow. And here, of course, at the beginning of spring, it was all green, the new vegetation growing hopefully on the rotting remains of those of years past.

I began to make my way slowly among the huts, in a necropolis-like silence, barely disturbed by the occasional bird's song. Someone had told me to be wary of wild boars, and indeed you noticed the very official sign warning of their presence in the first photo of this story—where it specifies that they must not be fed, which initially suggests they are quite friendly… Nevertheless, I know that these beasts can be ferocious, especially when they have piglets (which was certainly the case at this time of year), so I kept a close eye on the ground, and several times I went to look for droppings, without, however, seeing so much as the tail of a boar. And apart from me, of course, not a soul in sight.

The huts themselves closely resembled those I had known and lived in. I don't know how long the material they're made of lasts, but most of them were still in very good condition and seemingly quite sound, except for some roofs slightly battered by the winds, which are always fierce near the Strait of Bonifacio. Most of the nameplates were more recent than "mine," but I was moved to recognize some whose design was undoubtedly the same as that used in the past. Who knows, perhaps some of these huts were exactly the ones I had known fifty years ago, their straw walls, seemingly fragile, still holding up perfectly despite the accumulated winters?

A "recent" house sign, with italicized lettering

A "recent" house sign, with italicized lettering

"Old" case: its plaque, once blue, has lost its color and its letters are straight

"Old" case: its plaque, once blue, has lost its color and its letters are straight

The changes, however, were numerous and striking for an "old-timer" like me. Right from the front door, the first shock: while "my" huts had only a sliding brass latch, or even, sometimes, a simple nickel-plated hook threaded onto a curved eyelet, suddenly all these "modern" huts were fitted with a solid latch designed to be padlocked… and indeed, most of them were! Fortunately, a few were open, saving me from having to break in… and then, the second shock: the floor was no longer just a simple concrete slab (or even, as I had experienced, packed earth!), but a lovely, well-laid tiled floor, which I can attest has held up well over time, even after seven years of neglect!

Almost all the lockers are thus secured with padlocks

Almost all the lockers are thus secured with padlocks

The interior of a hut abandoned for eight years: dirty, but perfectly dry. Luxury wardrobe (!) with a strong cassette.

The interior of a hut abandoned for eight years: dirty, but perfectly dry. Luxury wardrobe (!) with a strong cassette.

Looking up, I noticed that the furnishings, too, had changed considerably: admittedly, the beds remained what they had always been, that is to say, basic, but there were now two wardrobes per cubicle (whereas before, only the most despicable hoarders—or those with connections—displayed such luxury), and what's more, each one was officially equipped with a secure safe, also ready to be padlocked, in which the Club very officially recommended not to leave more than 250 euros in cash, and 2,500 in jewelry and other valuables…! I was dumbfounded. Had the Club really needed money? Didn't everything just be deposited in the village safe upon arrival, as before? Were those great social class levelers—the bar collar and the fear of theft (human nature remains what it is, alas! even at the Club)—no longer there to contribute to creating that wonderful atmosphere we had known and so cherished? Could one now leave one's Cartier watch in the "safe" of one's cubicle and proudly display it to the envy of others at the bar in the evening, hoping to compensate for mediocre performances in archery, water polo, or pétanque earlier in the day? Had the Club changed that much?

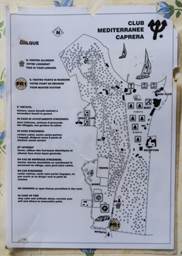

It certainly seemed so: in each hut, they'd felt compelled to display a laminated map of the village (I kept one as a souvenir; it had fallen on the floor), whereas before, we managed perfectly well without one (when we didn't know something, we asked, which helped build connections!). The odious precautionary principle, which infantilizes and absolves us all of responsibility, had struck again, and besides, hadn't they gone so far as to equip each hut with an electric ceiling light? Why not a jacuzzi and an iPhone dock while they were at it?

The village map, in case you get lost…

The village map, in case you get lost…

I emerged from that first hut, perplexed. What I had seen there told me a great deal about how the Club, its spirit, its atmosphere, had evolved. All these new arrangements undoubtedly represented a certain "progress." The advantage of electric light was undeniable, saving the more prepared guests from having to bring the famous blue Campingaz lamp, very effective and not very attractive to insects (in fact, any reasonably well-equipped GM also arrived with six strips of mosquito netting pre-cut to the correct dimensions, a small hammer, and nails, to protect the openings of their hut in case it hadn't already been done). But it was undeniable that open-flame lighting, even with excellent protection, and giving off heat, was not ideal in a hut that was inherently highly flammable (including the roof!), itself situated among other similar huts in an environment also very susceptible to fire.

A strange "family" house, the only one in the village

A strange "family" house, the only one in the village

The entrance "vestibule" to the family home: one room to the right, one to the left

The entrance "vestibule" to the family home: one room to the right, one to the left

Continuing my walk, exploring to the right and left, I came across my first "sanitary block," as we called these communal units back then, housing sinks, showers, toilets, laundry tubs—in short, the only water sources (always potable, even if it sometimes didn't taste very good) in the village, apart from the restaurant, the bar, and the activity areas. While in the huts, bed frames, mattresses, and wardrobes had been gathered in the center (to discourage insects from nesting?), but left in place, in the sanitary block, everything that could reasonably be dismantled had been taken away: faucets, plugs, pipes, traps—everything was gone, without any apparent vandalism, without brutality, without damage, as if the dismantling had been deliberately carried out calmly and methodically after closing time. However, the pipes were all supposed to be PVC, and the taps chrome alloy, no copper in any of it, but perhaps it still had some value that I was unaware of, and that the Club had wanted to realize before leaving the premises…

This first encounter with solid walls confirmed what I had suspected from other photographs before my departure: that everything I had known painted a simple, Mediterranean white had since been covered with a rather unpleasant, egg-yolk yellow that had aged poorly. The village chief's hut, which I had the honor of entering on several occasions, had suffered the same unappealing whitewash, peeling off in large patches and revealing the white underneath, which was apparently of much better quality.

I was entering the pine forest at that moment, and perplexity assailed me again: there were no huts under the pine forest! They were spread out to the side, tiered as I remembered them, all the way behind the bar and all over the small promontory located behind the sailing hut, but under the pine forest itself, nothing! The perspective was quite beautiful, but it did not correspond at all to my memory.

So, either the houses previously built under the pine forest had been removed (probably for fire safety reasons), or the pine forest had once extended into all or part of the southern part of the village, between the offices and the parking lot, to simplify, and for some reason no longer existed, having been replaced by various tree species. Perhaps a GM who reads this account will be able to provide me with an explanation for this mystery…

Not far from the village chief's hut (but closer than I remembered), I found the building of what used to be called the "Offices": Management, Cashier, Traffic, Planning, etc.

A special room, next to the offices…

A special room, next to the offices…

What was it used for? For the hostesses?

As I approached, I had a moment of emotion when I found, in exactly the same spot, the small stone table and the four small square seats that surrounded it, where I had so often sat to write. Apart from the yellowish whitewash, nothing had changed at all; for a moment, I had just taken a leap into the past more than twice over , which brought me back with incredible vividness to my memories of young adolescence: the smell was the same, the objects were the same, down to the cracked mosaic fragments, and even the tree trunks didn't seem to have changed, even though they must have aged, just like me, half a century in the meantime!

Exactly as I remember it… nothing has changed in fifty years (except the color)

Perhaps a maritime pine tree rounds out less quickly around the waist than a so-called Homo sapiens?

After this emotional and temporal shock, I explored the Offices. Unlike the cubicles, which had seemed, relatively speaking, to be in very good condition, still sound and very dry despite the rain that had fallen since the previous day, the solid buildings of the Offices surprised me with their advanced state of disrepair. Part of it was even cordoned off with barrier tape, and " Danger of Collapse" had been posted everywhere. And everywhere, doors and windows were carefully closed. As an urban explorer respectful of his code of ethics, I didn't break in and decided that any secrets that might be hidden behind those doors would remain untouched.

A rather incongruous payphone

A rather incongruous payphone

in this silent solitude

Continuing my peaceful walk under the pine forest, and now completely forgetting those wild boars that had worried me a little at the beginning, and which I knew preferred thickets to open ground, I headed towards another mysterious place in the village, where I had only been admitted once, and which I was preparing with delight to have for myself alone: the Equipment.

I don't know about villages today, but in the hut villages of the last century, there were always things to fix, little repairs to do, a part to replace on a diving compressor, fiberglass to mend the hull of a dinghy that someone else had badly dented, and so on. All of this, and much more, could be found in that treasure trove that was the hardware store. They had everything (or pretended to), and knew how to do everything (ditto): tools, materials, raw materials, sophisticated mechanical and electrical installations, carpentry, plumbing, plastering—every trade the village might need to function was represented there.

Of course, the GMs had no right to be there, and even the GOs only approached with a kind of respect that they tried to conceal under a boastful air.

I cautiously entered myself, not out of respect for tradition, but because I thought that if there was still a guardian in the village, that's where he would be. And from a Sardinian guardian, neurasthenic and disoccupato, anything was possible. While I hadn't believed the story about the CCTV, the concept of the old Sardinian, invested with an almost mystical mission as guardian of this abandoned temple, and also a hunter like all old Sardinians (and therefore, armed with a rifle), remained firmly in my mind.

However, nothing of the sort happened, and the Equipment Store proved to be just as deserted as the rest of the village. These places, admittedly rather dirty, and now devoid, with the exception of an old, rusty industrial washing machine, of all those mysterious machines, pots and bags, and other complex tools (at least to my adolescent eyes) that had built its myth, rather disappointed me. I barely noticed the presence of two small scooters and an electric golf cart, all of them rusted and dilapidated beyond belief.

Access to equipment outside the village.

Access to equipment outside the village.

Note the reference to "members wearing bracelets": so we were chipped at the Club in recent years?

G.O. accommodations . Equipment

G.O. accommodations . Equipment

Interior of one of these dwellings

Interior of one of these dwellings

More than the girl's buttocks, what's interesting here

More than the girl's buttocks, what's interesting here

is this collection of badges that the GOs were probably wearing.

Continuing my descent towards the sea, which I had been seeing sparkling for a while between the pine trees, I reached the restaurant.

Let's continue our descent towards the sea, which can be seen beyond the pine trees…

Let's continue our descent towards the sea, which can be seen beyond the pine trees…

The restaurant: in the past, this space was filled with tables and benches

The restaurant: in the past, this space was filled with tables and benches

Original paving of the restaurant

Original paving of the restaurant

The kitchens, restaurant side: behind these counters were the grills, the barbecues.

The kitchens, restaurant side: behind these counters were the grills, the barbecues.

How small it seemed to me, stripped of its tables and benches, whereas it had appeared so vast when I had to walk through it among the hundreds of diners! How silent, sad, lifeless it was, when I had known it to be so lively, buzzing, full of scents and flavors…! Yet, it had hardly changed: beneath the thick carpet of pine needles, I could see the flagstone floor I recognized, the very one I had often walked barefoot on, and in a corner, I found the poignant fragments of a broken dish and plate, abandoned for years, whose colors, too, spoke to me across the decades that had passed… So many memories, long buried, but suddenly revived by the contemplation of a few poor fragments of cheap porcelain!

I stood there, arms hanging limply, unable to tear myself away from this poor treasure, wondering whether I should first head towards the bar, or rather towards the nearby beach, whose access I could now clearly see was no longer blocked by that orange fence, all trace of which had disappeared… If I had known, I would have come directly that way…

The old volleyball courts, the bar and dance floor at the back, and the sea to the right, without any barriers…

The old volleyball courts, the bar and dance floor at the back, and the sea to the right, without any barriers…

I was at this point in my thoughts when I saw a small black Fiat appear from the far end of the village, driving at a good speed, clearly driven by someone who knew the area. At first, I thought it was a local visiting, and wondered how he could have possibly avoided the bad track at Cala Garibaldi. Then, when he got out of his car, waving his arms around dramatically, and I could read the word "VIGILPOL" on his black shirt, I realized I'd just been caught red-handed.

Negotiations would have to be done… Italian style.

Cala Garibaldi beach. If you look closely,

Cala Garibaldi beach. If you look closely,

you'll see, on the left, under the pine trees, the security guard's car…

END OF PART ONE

Hello; I first came to the club in 1982… so many wonderful memories from those almost two months. The atmosphere was superb, and in the evenings the bar brought us together. A few mornings, a headache… the grappa had taken its toll. We danced a lot and participated in the various shows, always well guided by the GOs (Gentils Organisateurs).

🎶💕🎶👏👏👏

The accommodations suited us, and the GOs were fantastic.

It's a shame that everything is falling apart a bit.

La Maddalena was very welcoming; I appreciated that hospitality.

Best of luck with your various endeavors, and I'm not the only one feeling a bit nostalgic.

Sincerely, Nina (from Brittany) 👏👏👏

Hello, I was a trainee lighting technician at the GO (Gentil Organisateur) for three months sometime in 1980/82, I don't remember exactly. There was a great atmosphere; the village chief was Machepro, a well-built and very friendly woman.

I continued for two more seasons in Wenguen in the mountains before finishing up at Les Restanques near Saint-Tropez. So many good memories…